This past week in my class on race & media, I led a discussion about industrial discourses surrounding racial casting. We read Kristen Warner’s (2015) study of color-blind casting in Grey’s Anatomy and problematized the idea of blind-casting through her argument that it serves to create representations that let white viewers feel good – soaking up the fantasy of post-racism, absolving the media industry of the sins of the past, and enjoying the safety of sanitized, purely cosmetic, plastic racial representation. We asked, what do racial representations do when they are not busy protecting white audiences, when they strive to truly prioritize and resonate with Black, Latinx, Asian American, and Indigenous audiences?

We thought about other recent examples and shifting racial casting practices, too. What do we make of the highly intentional and self-reflexive racial casting of Black Panther as the first Black superhero movie? Or the claim to national belonging through the race-bending of Hamilton? Or the dream of racial equality depicted in the utopic police force of Brooklyn Nine-Nine? What are these texts doing? Who gets to feel good when they watch them and what are the politics of that good feeling? Whose feelings are central and whose are an after-thought? These are big questions, and they led to a provocative discussion, though perhaps unsurprisingly we ended up with more questions than answers.

We thought about how these texts allow many audiences to feel good, and, with a little prodding from moi, we started to problematize the racial hierarchies of that good feeling. For instance, students could not definitively agree on who Black Panther was for, determining it was consciously addressing Black and white audiences, and a global market, too. Even when the text, its creators, and audiences celebrated the film as unapologetically Black representation, to what extent did whiteness creep its way in? To what extent did the fear of alienating of white audiences shape the text? Or how did white viewers engage with the film and its racial politics? Did white viewers reactions to Black Panther mirror white viewers reactions to The Cosby Show, which Justin Lewis and Sut Jhally (1992) theorized as “enlightened racism”? How did the production of a Black superhero film within the franchise of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the representation of Black characters on-screen feed into neoliberal post-racist beliefs of white audiences that the industry and US society are no longer shaped by racial discrimination? Or were white audiences actually made to feel uncomfortable and alienated by this text?

We then turned to one of the most recent controversies in racial casting — The Little Mermaid. Students listened to an episode of the Black Girl Nerds podcast called “‘The Little Mermaid’ Nontroversy” in which they discussed the racist fan responses to the announcement this past summer that 19 year old actress and singer Halle Bailey had been cast to play Ariel in Disney’s upcoming live-action remake of The Little Mermaid. We considered the backlash as an example of white viewers’ feelings of entitlement to this representation, and how Disney’s attempts to demonstrate it has changed and is now being intentional about racial representations is profit-motivated. But, after listening to Jamie Broadnax, Ryanne Bennett, and Anjelica Monk discuss their reactions to news of the casting, we reflected on the reasons why this casting is a real cause for celebration, why it offers true pleasure and joy for Black audiences to see themselves. We discussed all the hopes and anxieties that get mapped onto the text, even before it is created, simply in the news of the casting. And we thought about ways it might disappoint or fail to live up to those expectations.

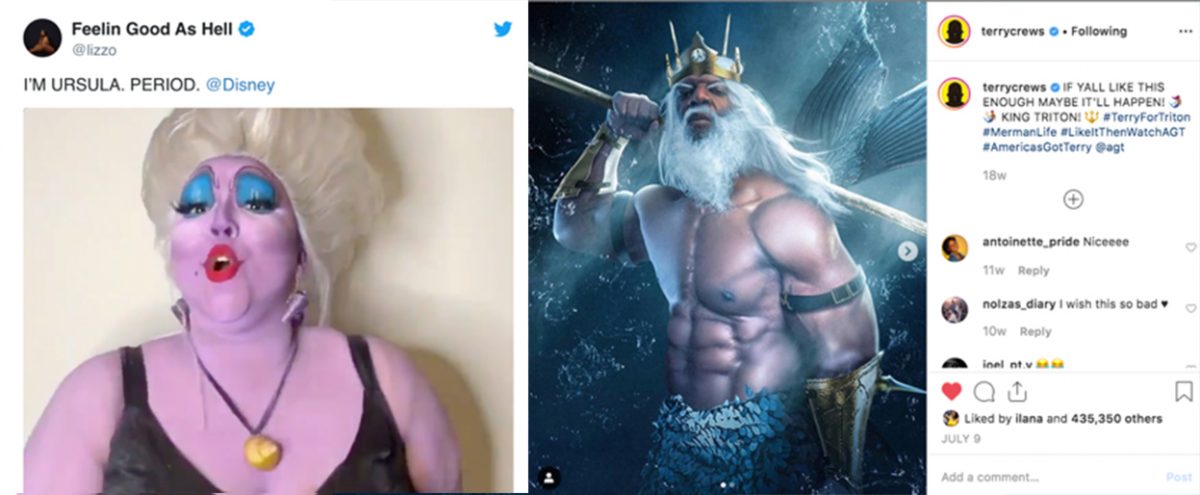

For instance, in the midst of white fans expressing outrage threw the hashtag #NotMyAriel, Black reporters and fans got to work imagining what they hope to see in the film, creating fan art and fan casting the other roles in the film with all Black performers. Black celebrities also participated, such as Lizzo who tweeted an audition video for Urusla and a series of posts by Terry Crews on Instagram about how he wants to play King Triton.

Rumors also circulated that the viral video of Titus Burgess’ 2016 performance of “Poor, Unfortunate Souls” might give him a shot at being cast as Ursula and reflected on the relationship between the character Ursula and drag queens. And still others speculated that Queen Latifah, already set to play Ursula in ABC’s The Little Mermaid Live!, would be cast as Urusla. Fans excitement about the latter was renewed following glowing reviews after the program aired on November 5.

However, so far, the call sheet for the rest of the cast includes Jonah Hauer-King as Prince Eric, Melissa McCarthy as Ursula, Javier Bardem as King Triton, Awkwafina as Scuttle, Jacob Tremblay as Flounder, and Daveed Diggs as Sebastian. It is a racially diverse cast, and it doesn’t quite seem to subscribe to color-blind casting or total race-bending. This ambivalent positioning makes it hard to argue that this cast is truly giving us anything above post-racial ideology. So, in many ways, despite such promise and intrigue, we end up back where we began, asking ourselves if this cast reflects an investment in neutralizing diversity, even stirring controversy and backlash amongst white viewers as a kind of promotional testament to Disney’s newfound progressive racial politics, without fully ever turning its attention to the desires and interests of Black audiences. And that is a disappointment that isn’t so surprising to media scholars but one that I think we can all do more to feel as we work to understand emerging industry practices, and to give our students the context and tools to really feel for themselves.