The opening credits of David Gordon Green’s sequel to Halloween directly mirror the original – John Carpenter’s iconic theme song plays against a black screen, the camera slowly zooming in on a jack-o-lantern. Only, in Green’s film, the pumpkin starts off rotten and regains its shape as the credits roll, ending up not quite as pristine as the one in Carpenter’s 1978 classic but close to replicating it. There is an immediate sense of revitalization for the franchise, one that has spawned eleven entries, including two Rob Zombie-helmed reboots in 2007 and 2009, and helped pave the way for the slasher franchises that dominated horror in the ’80s.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens ushered in a new trend of long-awaited sequels and franchise reboots becoming almost entirely about their ow intertextuality, revisiting and interacting with their predecessors. The Last Jedi was controversial to some fans for, among other reasons, its lack of interest in the established history and mythology of the Star Wars franchise, as well as the many theories proposed by fans between Episode XII and XIII. Halloween (2018) follows a similar path, but was met with much less resistance. Rather than try to sort out the convoluted narrative and backstory created by the many sequels, they have been retconned out of the timeline in which this new entry exists. Considering the progressive dilution of quality in the sequels, most long-time fans welcomed this decision with open arms.

And yet, Halloween can’t seem to let go of its past. Because it is a direct sequel to Carpenter’s original, there is an unsurprisingly large number of callbacks that often drift into overt, lazy fan service. This was a massive annoyance of The Force Awakens, but It’s far more damaging to the narrative of Halloween, undermining its only interesting plot thread – Laurie’s PTSD.

It’s impossible to discuss this aspect of the narrative without mentioning Zombie’s Halloween (2007) and H2. The Hollywood Reporter recently ran an excellent article reevaluating these films as horror remakes, which tend to be uninspired and boring. Love him or hate him, Zombie has a distinct vision for his film that distinguishes them not only from the countless horror remakes that flood the market, but also from the rest of the Halloween franchise. One of the biggest gripes with his Halloween, however, is the inclusion of an origin story for Michael Myers, who Carpenter has always posited as a being of pure, simple evil. Zombie gave him a broken home and tragic backstory. In H2, Zombie shifts his focus toward Laurie, who is (in the tradition of 1982’s Halloween II) Michael’s sister, exploring the effects of both the trauma Michael has afflicted on her and the hereditary nature of Michael’s evil being passed on.

A young Michael Myers stands over his first kill in Zombie’s Halloween

Green’s Halloween is engaging with both of these ideas to an extent. Although it has disavowed both Halloween II and its assertion that Laurie and Michael are related, it is working through the 40 years of trauma and PTSD that the former has experienced because of the latter. This most often takes the form of drawing parallels between the two through recreations of scenes and images from the first with Laurie taking Michael’s place. For instance, when Laurie’s granddaughter Allyson looks out at the window at school, she sees Laurie standing outside watching her, just as Laurie saw Michael in the original.

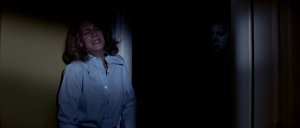

Two other major examples occur during the climax. The first is when Laurie is thrown over a second-floor window by Michael. Mirroring Donald Pleasence’s Dr. Loomis in the original, he looks down to see her sprawled on the ground unmoving, but when he is distracted by sounds elsewhere in the house, she’s disappeared by the time he looks back. The second plays on the iconic image of Michael’s mask coming out of a dark closet, just over Laurie’s shoulder. In this new iteration, it is Laurie who materializes out of the shadows as she helps deliver the “killing” blow on Michael.

Michael Myers prepares to attack Laurie Strode in Carpenter’s Halloween (1978)

Michael Myers prepares to attack Laurie Strode in Carpenter’s Halloween (1978)

Of course, Halloween is engaging with Laurie’s trauma in other ways by haphazardly showing us the strain it has put on her relationship with her daughter (played by Judy Greer, who continues to be criminally underrated and has one of the best moments of acting in this film) and granddaughter. But it’s far less interested in developing this than it is with nudging us during the movie and whispering, “hey, remember this thing from that movie you love?” This abounds in visual cues and lines – not to mention Carpenter’s score, which has been largely retained – that bring forth memories of the original film and even some of its lesser-revered sequels, including a reference to Halloween III: Season of the Witch, the franchise’s lone anthology film that has nothing to do with Michael Myers. At one point, Laurie even says to Dr. Sartain, Michael’s new psychiatrist, “so you’re the new Loomis.” It’s a frustratingly transparent way to get audiences to like a subpar sequel.

Even more transparent is its response to the Zombie films, and to Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, which also attempts to explain Michael’s evil. Our entry into the film is via two true-crime podcasters trying to find answers about the original murders in Haddonfield. For some reason, they’re invited into the psychiatric hospital where Michael is kept. They’re allowed to wave the iconic mask – which they somehow have, without much explanation given to the audience – at him and scream at him to say something. They are two of the earliest people killed, and arguably two of the most drawn-out and brutal deaths in the film. Dr. Sartain, who is just as obsessed with what drives Michael, similarly tries to force the killer toward a moment of clarity later in the film. When Michael gains the upper hand on him, the doctor again repeats the line, “say something,” before having his head curb stomped like a pumpkin. It’s no coincidence that this is the only moment of violence that comes close to Zombie’s work.

The ending of Halloween (2018) is curious and frustrating. Just as Laurie had to use Michael’s butcher knife against him in the original, Allyson does so when helping her mother and grandmother fight The Shape. When the three women ostensibly kill Michael and escape via a passing truck, the final shot of the film zooms in on the knife, still in Allyson’s hand. There is a strong sense of trauma continuing to be passed down through the shared experience of having survived Michael’s rampage. It’s an interesting thought that further develops Laurie’s characterization without heavy-handedly referencing the original; the shot immediately preceding it is the burning basement in which Michael is supposed to be trapped. He’s nowhere to be found, and his heavy breathing, the same that punctuated the original film, is heard after the end credits have rolled. It’s unclear if sequels will be made, but Carpenter himself recently said that he’s “up for anything that involves money,” and Halloween brought in over $77 million at the box office its opening weekend, so it seems likely that one will be made. If that’s the case, the Halloween franchise will find itself going down a path that it has already taken, a path that was just decanonized by its newest film.