When Roseanne was rebooted in 2018, it garnered ratings assumed near-impossible for a broadcast sitcom during our era of “Peak-TV”. A maelstrom of controversy and conversation followed the series’ announcement, cancellation, and second reboot as The Connors, due to star Roseanne Barr’s support of Donald Trump, belief in right-wing conspiracy theories, and frequent racist Twitter outbursts. While the case of Roseanne is extreme given the polarizing nature of its star, it is not surprising that a reboot of a beloved television series should stir strong emotions in fans and an outsized reaction in the cultural zeitgeist. To explore why this is the case necessitates looking beyond the purely economic explanation for reboots’ recent popularity, i.e. that name-brand recognition sets these series apart in a sea of television programming and come with a built-in audience. It also requires adding a layer to the idea that these series’ appeal lies in nostalgia. While certainly a factor, nostalgia suggests romantically looking backwards, perhaps even imagining something that was never truly there. The audience reactions I am most interested in are those that suggest an ongoing relationship with the text that has evolved over time. The reaction to the rebooted Roseanne was overwhelmingly negative not only because of Barr herself, but also because this new Roseanne and Roseanne betrayed what the show once seemingly stood for and for which it continued to have a legacy long after it ended its initial run. A show that once explored the intersections of feminism and class with care and nuance now had Roseanne abusing her grandchild and making jabs at fellow sitcoms that carry on Roseanne’s original legacy.

It is not the sound business logic of a reboot that has audiences returning and engaging with fervor. It is strong affective and identificatory ties between viewers and characters, ties that have been nurtured in various ways in the intervening years. Television’s typical practice of releasing episodes periodically over several years creates a bond between viewer and character in which the character’s life feels as though it is unfolding in real time, and thus “checking in” with them years later is depicted inter- and extra-textually as a natural progression of said life. Fan engagement platforms such as the AV Club’s retrospective reviews or new podcasts discussing past series help to maintain this bond and facilitate conversation amongst fans years after series have left the air. Returning to the life of a once-beloved character is a major draw for fans, but it can have adverse effects should the reboot not be received as a believable or satisfying extension of the character(s) because the show has now broken points of audience identification.

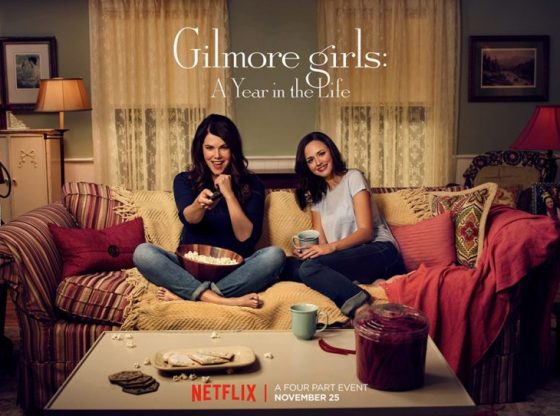

To use a less politically loaded example, in 2016 Netflix revived the WB series Gilmore Girls as a four-episode event series. Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life immediately calls on the affection of viewers for our titular girls in its opening sequence. Laced with meta references and quintessential iconography from the show, the first scene essentially functions as a “welcome back” to the fans. However, any warm feelings this opening may have elicited quickly dissolved for many viewers as the series progressed. It turns out that the once precocious, type-A Rory (Alexis Bledel) became adrift in adulthood, carrying on an affair with her engaged ex-boyfriend and seemingly having no grasp on her chosen profession of journalism. The character many teenage girls once identified with in her formative years on the WB is a disappointment to check back in with. The strong affection fans felt (and perhaps still feel) for Rory became laced with negative feelings when that affection was not rewarded and the ways in which they identified with her were broken.

This reaction is compounded by several factors. First, that Gilmore Girls enjoyed a robust afterlife in such forms as periodic thinkpieces and listicles, the popular podcast “Gilmore Guys,” and success in second-run syndication. Secondly, the mythos that surrounded the original series run also aided both fan speculation over the years and anticipation for the new series. After creator Amy Sherman-Palladino’s contract negotiations with the WB broke down for the seventh season of Gilmore Girls’ original run, she was not involved with the show during its final season. While reactions to the seventh season are mixed among fans, it was the consensus that at the very least the series was never finished “correctly” because Sherman-Palladino infamously declared she had always known what the final four words of the series would be but never got to execute them. Thus, with Sherman-Palladino again at the helm, the reboot was not only framed as a check-in on these characters’ lives, but a long-awaited catharsis to years of musing about what could have been. Given the high expectations and significant letdown felt by many fans, especially in regards to the character of Rory, the revival was primed to receive strong, emotional responses from fans.

While Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life and Roseanne are distinct examples, both demonstrate what can be illuminated by fan reactions to a reboot. They can illustrate industrial practices of gauging audience reception to help mold years-long character arcs. When are audiences’ reactions taken into account by showrunners when crafting these stories over time, and when are they ignored? What are the repercussions of ignoring or listening too closely to fans when one has years, even decades, of feedback to consider? These story arcs and fans’ reactions to them can also illuminate cultural understandings of what constitutes successful, or at the very least realistic, personal growth and aging. Rory’s floundering in both her romantic relationships and profession at the age of 32 is clearly disappointing to fans, showing that the opposite is expected of those given the advantages of wealth and education. There was no such outcry over the similar way audiences are re-introduced to Roseanne’s Darlene (Sara Gilbert), after all. Given that the trend of making old TV new again shows no sign of slowing down, television scholars must consider how the medium and its paratexts inform narrative, character and the impact of a fans’ long-term relationship with both.