While there have been many films with LGBTQ characters/narratives/themes released to critical acclaim and relative box office success over the last couple of decades, almost all of them were distributed and marketed as essentially prestige pictures. Titles like Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005), The Kids Are All Right (Lisa Cholodenko, 2010), and Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016) eventually expanded to hundreds or thousands of theaters on the strength of Oscar buzz and strong reviews, but their initial placement within the cultural and economic market framed them as art-house or “indiewood” titles aimed at more “discerning” filmgoers. What we haven’t seen, in short, are wide-release, mainstream films centered around LGBTQ characters. One has to go back to the mid-to-late 1990s to find a sustained period in which such titles existed in Hollywood: To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (Beebee Kidron, 1995), The Birdcage (Mike Nichols, 1996), In & Out (Frank Oz, 1997), The Object of My Affection (Nicholas Hytner, 1998). Certainly, the aesthetic and/or ideological value of said titles are open to debate, but the sheer breadth of their reach gave them a visibility that many of the smaller, more targeted LGBTQ titles of recent years cannot compete with.[1]

Within this context, then, Love, Simon (Greg Berlanti, 2018) represents the first significant attempt by a major studio to widely distribute and market a film centering on LGBTQ characters and themes. Briefly, the film follows Simon (Nick Robinson), a closeted high-schooler who begins to communicate online with a fellow closeted teenager who attends Simon’s school and goes by the pseudonym “Blue.” These e-mails are eventually discovered by another classmate, who threatens to out Simon to the school unless Simon assists his blackmailer in helping secure a date with one of Simon’s friends. Featuring such youth-courting cast members as Katherine Langford (of 13 Reasons Why (Neflix, 2017–present)) and made under the auspices of YA-driven production company Temple Hill Productions, Love, Simon has been positioned fairly unambiguously by distributor 20th Century Fox as occupying the generic ground as such recent teen-centered hits as The Fault in Our Stars (Josh Boone, 2014). Its planned release in 2,400 theaters further backs up the assumption that Love, Simon is a film aimed at the masses.

Which leads to the inevitable question: what, exactly, are they trying to sell? More specifically, what does it look like to frame a film about closeted youth and burgeoning LGBTQ identity both as a mass-market product and within a political climate far removed from the 1990s (i.e., the last time that major studios tried to sell LGBTQ images to the public)? The full intricacies of 21st -century movie marketing—particularly the strategies behind digital publicity and outreach—remain beyond the scope of this post, but I do think it’s telling to consider the two more-traditional avenues through which studios frame their titles for the world: posters and trailers. Love, Simon has two of each—an initial poster and trailer released in the fall of 2017, and a revised poster and expanded trailer put out in January 2018. Examining these two marketing moments side-by-side, what’s most striking is a subtle shift in emphasis. While the first poster and trailer lean heavily on the vicissitudes and anxieties surrounding the closet in 2018, the second poster and trailer reframe Simon’s journey as one of self-acceptance as the path to the ultimate goal: young love. In doing so, it moves the film’s core appeal from the more amorphous questions of self-identity surrounding the coming-out process to the more immediately relatable issue of finding romance.

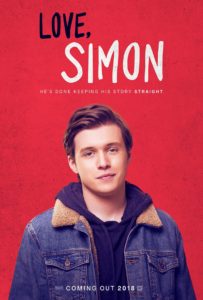

The film’s initial poster puts the notion of coming out as a liberatory stand against self-deception front and center, albeit in winkingly coded terms. “He’s done keeping his story straight,” proclaims the poster’s tagline, which rests above a photo of Simon gazing serenely towards the viewer, a small smile on his face. When framed further within the film’s first trailer, however, two things stand out regarding Simon’s closeted nature: the lack of obvious external factors that pressure him to keep his sexuality hidden; and the intriguing acknowledgment of coming out as a process that encompasses both losses and gains. No clear impediments to acknowledging his sexuality are made apparent as Simon narrates via voiceover the details of his teenage life. (Indeed, the one clear narrative conflict that sets Simon on the path to coming out—the aforementioned blackmail scheme—is not mentioned in the first trailer, and only glancingly acknowledged in the second.) The most clearly articulated barrier to coming out is actually voiced by Langford’s character, who muses about an “invisible line that I have to cross to really be a part of everything and, just, I can’t ever cross it.”

The film’s initial poster puts the notion of coming out as a liberatory stand against self-deception front and center, albeit in winkingly coded terms. “He’s done keeping his story straight,” proclaims the poster’s tagline, which rests above a photo of Simon gazing serenely towards the viewer, a small smile on his face. When framed further within the film’s first trailer, however, two things stand out regarding Simon’s closeted nature: the lack of obvious external factors that pressure him to keep his sexuality hidden; and the intriguing acknowledgment of coming out as a process that encompasses both losses and gains. No clear impediments to acknowledging his sexuality are made apparent as Simon narrates via voiceover the details of his teenage life. (Indeed, the one clear narrative conflict that sets Simon on the path to coming out—the aforementioned blackmail scheme—is not mentioned in the first trailer, and only glancingly acknowledged in the second.) The most clearly articulated barrier to coming out is actually voiced by Langford’s character, who muses about an “invisible line that I have to cross to really be a part of everything and, just, I can’t ever cross it.”

This frames Simon’s reticence within the larger context of teenage self-doubt and isolation—a strategy that bleeds into the broader situating of Simon’s sexuality as the single distinction that differentiates him from every other teenager. “I’m just like you,” Simon insists to the audience, “except I have one huge ass secret.” Certainly, constructing the audience’s conception of a gay teenager as “just like you” in every respect save one loops into a broader homonormative cultural discourse that seeks to figure LGBTQ people as “virtually normal” (to borrow Andrew Sullivan’s phrase) when compared to straight people.[2] Furthermore, centering the narrative around a protagonist who otherwise embodies normativity—white, middle-class, cis-gendered, masculine-presenting—both allows such a move and positions Love, Simon within a broader history of coming-out narratives that have been critiqued by both critics and scholar for their overly restrictive representation of LGBTQ identity and experience.[3] Still, it also opens up some intriguing space in how the film sells the idea of coming out to its audience. “I’ve been thinking about why I haven’t come out yet” Simon muses as we see him walking through school and hanging out with friends. “Maybe, part of me wants to hold on to who I’ve always been just a little longer.” This may rest on certain privileges that an individual like Simon possesses, but it also adds an intriguing wrinkle to popular conceptions of the closet as simply a suffocating prison that is eventually broken out of the notion. Publically redefining yourself, the trailer seems to imply, requires losing something of yourself even as you reveal other, long-shrouded realities about who you are and how you exist in the world.

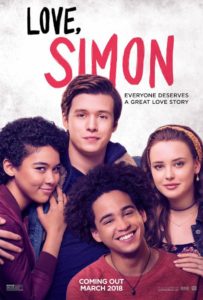

The closet as ambivalent cage does not disappear from Love, Simon’s marketing as its second poster and trailer were released, but it began to take a backseat to the notion of romantic love as the implicit end goal of any coming-out narrative. What these marketing materials seem to selling, however, is not any particular romantic situation for its protagonist so much as the generalized concept of inclusive romance. This shift can be seen in the revamped poster design, which moves from the single image of Simon and a tagline winkingly pointing to his coming out narrative to a group shot of Simon flanked by his three friends and the revamped tagline: “Everyone deserves a great love story.” Given that it’s a bit unclear whose love story we’re talking about from the visual cues alone, the sentiment moves beyond Simon’s “love story” and into the more general realm of liberal-minded sentiment.

The closet as ambivalent cage does not disappear from Love, Simon’s marketing as its second poster and trailer were released, but it began to take a backseat to the notion of romantic love as the implicit end goal of any coming-out narrative. What these marketing materials seem to selling, however, is not any particular romantic situation for its protagonist so much as the generalized concept of inclusive romance. This shift can be seen in the revamped poster design, which moves from the single image of Simon and a tagline winkingly pointing to his coming out narrative to a group shot of Simon flanked by his three friends and the revamped tagline: “Everyone deserves a great love story.” Given that it’s a bit unclear whose love story we’re talking about from the visual cues alone, the sentiment moves beyond Simon’s “love story” and into the more general realm of liberal-minded sentiment.

This extends into the trailer as well. While certainly continuing to linger of Simon’s coming-out narrative, it more tightly links this to romance and affection more broadly. Another Langford line sets the tone, to which Simon once again concurs: “Sometimes, I think I’m destined to care so much about one person, it nearly kills me.” The curious thing, of course, is not Simon’s object of desire is not actually defined within the trailer. His growing affection for “Blue” (discussed as a plot point in the film’s reviews thus far) is not broached. And while Simon certainly casts amorous glances at a couple of guys, the climactic kiss that closes the trailer—paired with Simon’s warning that “this is about to get romantic as F”—is with a fellow teenager that has heretofore not been introduced as a character. What the trailer is selling, rather, is the notion of romance that’s democratic, accessible, and feel-good for all. Such a move reaches its apotheosis roughly two-thirds of the way through the preview, where Simon declares via voiceover: “I deserve a great love story, and I want someone to share it with.” It’s an exceedingly odd sentiment, the more it rolls around in your head. Why would Simon need to “share” his “great love story” with his would-be beau? Wouldn’t that other person be as a part of said love story as Simon? What constitutes the “great love story” beyond the involvement of the two people in it?

This, I think, marks the crux of Love, Simon’s attempts to define its vision of LGBTQ youth experience. Having found itself necessarily backed into one corner—how to dramatize the act of coming out when there are no obvious external narrative impediments to doing so—the film’s marketing proceeds to maneuver into another—namely, how to sell the idea of young queer love without lingering on the details of any specific coupling? That these efforts swerve between fumbling and genuinely affecting perhaps speaks to the evergreen challenges of selling LGBTQ experience to a mass audience whose reactions Hollywood simultaneously shapes and responds to. How these challenges get taken up within Love, Simon itself is something we’ll find out soon enough.

[1] The one significant exception to this trend is Bruno (Larry Charles, 2009), which centers on Sacha Baron Cohen’s flamboyant titular character that he originated on Da Ali G Show (HBO, 2000–2004) and was released in over 2,700 theaters on its opening weekend. While that film’s box-office performance and cultural reception deserve closer scrutiny, its roots in sketch comedy and approach to LGBTQ representation present a different set of questions than many of the other titles under discussion here.

[2] Andrew Sullivan, Virtually Normal: An Argument about Homosexuality (New York: Vintage Books, 1995).

[3] For an example of film-critical discourse that contains these criticisms, see Michael Bronski, “Positive Images & the Coming Out Film: The Art and Politics of Gay and Lesbian Cinema,” Cineaste 26.1 (2000): 20–26. For a scholarly critique, see Gilad Padva, “Edge of Seventeen: Melodramatic Coming-Out in New Queer Adolescence Films,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 1.4 (December 2004): 355–372.