What is fanfiction?

Answers to this question have spilled rivers of aca-fan ink, and past scholars and fans have offered all kinds of intelligent insight into the question. In these investigations, the primary criteria for a fannish determination tend to revolve around commerciality, transformation, positionality, and copyright.

However, in terms of practical application, the judgment of what is a “fan” work and what is a “real” (that is, professional) work of creativity sometimes seems to boil down to that old chestnut about pornography: you know it when you see it.

A sexually explicit piece of fiction posted to a free online archive about how Holmes and Watson are in love, living their best gay lives in 221B? Fanfiction.

A well-funded, officially licensed BBC production about John and Sherlock having purportedly heterosexual adventures in modern-day London? Professional television.

In the above example, several elements distinguishing the professional and the fan production come to the fore, namely, sexuality, commerciality, and officiality. If it’s queer, free, and not sanctioned by The Powers That Be, then it’s a fanwork. If it’s straight, costs money, and is approved by copyright holders, then it’s professional.

But what about when these lines blur?

Increasingly, fan and professional productions are borrowing characteristics from each other, and in fact, the two have never truly been historically separate. Fanfiction has always included a range of sexualities, and professional works are hardly all heterosexual. Fan productions, such as fanart, have often lived in a commercial realm, with posters, tote bags, and mugs featuring fanart of copyrighted characters, from Harry Potter to Captain Picard, selling online and by in-person vendors. Fan and professional productions have both borrowed from material in the public domain, thus avoiding copyright altogether, and fair use laws have protected both kinds of creators in their transformative reuse of materials still under copyright.

Perhaps most importantly, creators from all sectors have always been fans, whether or not they create or share their works in fannish spaces. For example, comic creators in particular have almost always been fans themselves; it’s practically a prerequisite to writing a series like Superman or Batman that you have a love for that character, and knowledge of their canon. So, fans have always been present in corporate spaces, and vice versa.

The question now becomes: if you’re a fan writing an official comic, or you’re a fan who’s also a graphic designer, and you’ve been professionally hired to make a movie poster for a franchise you love, what is it that makes the work you produce “art” rather than “fanart”?

Certainly, there are differences, mainly in the structural power and authority granted by or unavailable to the two positions of fan and professional. Here, what I’m trying to point to is the ways that the professional/fan binary obscures critical potential.

I propose that maintaining this strict binary isn’t productive, and instead, suggest that we investigate the messy, fascinating intersections of the fan and the professional. This blurry zone of creation offers new potential for subversion as well as new dangers of exploitation and replication of harmful hegemonic structures, and thus deserves exploration.

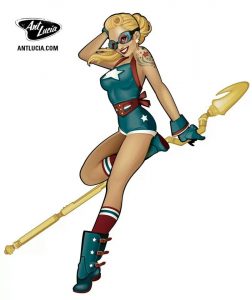

A specific example well-suited to illuminating this concept is the DC comic series Bombshells. The series was inspired by Ant Lucia’s vintage pin-up style artwork of DC heroines. This art was merchandised in a variety of avenues, and quickly became a huge hit with fans, inspiring DC to create the comic series.

Ant Lucia’s artwork of a pinup-style Stargirl.

Bombshells follows a female triumvirate of heroes, Batwoman, Wonder Woman, and Supergirl, as they join forces with a group of other female heroes to fight the Nazis in a supernatural, re-imagined World War II. All the main characters in this series are women, and nearly every one of them is queer.

This is a very fannish move; queering beloved characters and giving them agency and complex backstories where they’d previously been ignored and down-trodden in white, straight, male-centered canon. Adding to Bombshells’ fanwork-like appearance is its nature as a digital-first comic: as with most fanworks, Bombshells exists first (if not exclusively) online, making it physically and financially accessible to diverse audiences. Additionally, Bombshells is like a fanfiction AU, an alternate universe, setting familiar characters in unfamiliar settings (in this case, putting modern heroines in WWII).

So, can we understand a comic like Bombshells to be a form of fanfiction, specifically, a form of femslash?

Femslash is the fan practice of enjoying pairing women characters with other women characters. The term femslash is used to describe fan works, fan communities, and fan practices around F/F (female/female) pairings. It is usually understood as an offshoot of the term “slash,” which is the practice of pairing male characters with other male characters. However, femslash is a practice and a community of people with a history and culture all its own.

Bombshells fits neatly into this history, with its queer woman author, community of passionate women fans, and massively queer cast of diverse characters. And, by understanding Bombshells as a form of femslash, we can begin to see the places that fan and professional practices impact each other, for better and for worse.

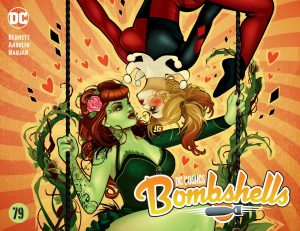

For example, Bombshells is wildly subversive of heteronormativity. It includes a wide range of relationships, from the domestic and monogamous relationship between Batwoman and her police detective girlfriend, to the playfully villainous love between Poison Ivy and Harley Quinn, to the twisted love triangle between Zatanna, John Constantine, and the Joker’s Daughter. This comic’s queerness seems indebted to a fannish history of queering all kinds of characters, no matter the stringent heterosexuality of their canonical origins.

Poison Ivy and Harley Quinn in love, on the cover of Bombshells.

Poison Ivy and Harley Quinn in love, on the cover of Bombshells.

However, Bombshells’ transformative energies seem to fade when faced with the whiteness and ablebodiedness of comic canon.

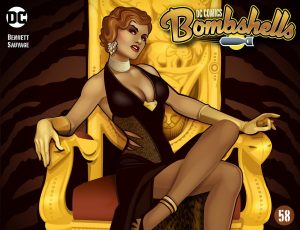

It’s not until almost twenty issues into the series that a woman of color even appears on one of the Bombshells’ covers (and that’s in a subordinate, background position), and it’s not until issue #58 that a woman of color is the central figure. This reflects fan problems with racism, in which reimagining Dean Winchester as bisexual is commonplace, but reimagining Hermione as black causes an uproar.

Vixen, the first Bombshell of color to have a cover in the series to herself.

Vixen, the first Bombshell of color to have a cover in the series to herself.

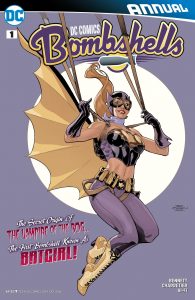

Similarly, Bombshells chooses to reimagine its 1940s pinup Barbara Gordon in her able-bodied superhero identity of Batgirl, rather than her wheelchair-using alter-ego, Oracle. Here, even a canonical disability is avoided, as professional and fan works alike tend to shy away from depicting disabled characters, or at best, fall into stereotypes like “the inspirationally disadvantaged” in their attempts.

Barbara Gordon as Batgirl.

Barbara Gordon as Batgirl.

Thus, accepting the blurring lines between different methods and communities of production allows us to see the ways that fandom and industry have impacted and interwoven their respective creative processes. Fandom may have allowed greater queerness into professional productions like Bombshells, but it brought with it its history of racism and ableism, which in turn was reflected from that of mainstream media. Similarly, corporations make inroads into fandom with events like fanmade poster contests and official fanfiction competitions that exploit fan labor with little to no recompense, while at the same time, this has led to mainstream acceptance and de-stigmatization of fans and fan practices, which opens fandom to greater numbers of folks who might not have had access to these tools and communities before.

In the end, maintaining a distance between the “fan” and the “professional” doesn’t just deny fans authority as creators by tacking on that often diminutive “fan” before their work, it also denies a fan identification to professionals; it denies the possibility that their work may operate more complexly than we’ve previously allowed for. By deconstructing this arbitrary division, we can start to see the ways fandom reflects problematic structures of racism/sexism/ableism, the way corporations exploit fan labor and communities, and the way these always already intertwined modes of production and distribution can influence each other for the better, not just the worse.