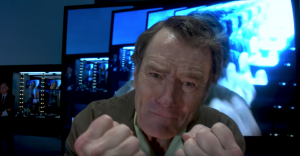

Bryan Cranston performing as Howard Beale in Network (National Theatre, 2018)

My first two Playback blogs were centered around exploring an area of media convergence that is academically understudied, which I believe offers a potentially rich forum for posing questions about the nature of artistic experimentation and medium specificity – that is, the convergence of film and theater in the 21st century. Why is it important to study this cross-section of media? It really boils down to the fact that we are moving in the direction of more hybridity in art, not less. Rather than bemoan the loss of “pure” media expression, I contend that when theater and film technology are brought in conversation, a whole new set of considerations and possibilities emerge for the study of performance and dramaturgy/narratology.

So far in the “Curtain Calls and Cameras” series (1 + 2), I focused on instances of filming performances for a cinema audience to watch either live (in the case of National Theatre Live) or on streaming platforms (like Spike Lee’s Pass Over on Amazon Prime). While these unique artistic texts push back against the association of filmed theatre with static wide-angle presentation, the most significant intervention they represent is the introduction of editing into a theatrical performance. Editing was often singled out by early film theorists as one of the definitive breaks film made with theater; the division of contiguous space with multiple cuts and the ability to jump between spatially disparate locations was viewed as a significant disruption of the unity that is intrinsic to the stage. With the increasing prevalence of cameras recording stage business and reshaping it with editing in post-production (a step that obviously doesn’t exist in the theater), the question of how film technology is re-shaping the stage right now is more vital to ask than ever.

Having explored theatrical performance captured for exhibition in spaces traditionally marked for cinema, I’d like to move on to consider how film technology is being incorporated into theatrical spaces as part of the production apparatus. Video/multi-media projection has been part of the fabric of set design for decades with notable early examples including artist Al Hansen’s 1960 production The Ray Gun Spex in which performers walked around onstage carrying handheld film projectors to create the illusion of airplanes and parachutists flying around the walls.

Since the 1990s, many directors experimented with multimedia projections including Julie Taymor, known for her innovative work in both theater and film. Taymor began integrating video and other multimedia elements onstage in shows like the 1998 production of Titus Andronicus which she later made as a feature film that retained vestiges of the digital projections (pictured below) and her 2013 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream which she then filmed for cinematic exhibition.

(click for video)

In a 2009 article, Patricia Milder argues that “video technology can no more be banned from the stage than it can be removed from our daily lives, and to the medium’s credit, in the right hands, the use of video in performance is illuminating on many levels, probing meaning within texts or revealing the ways in which the human body and mind process or compete with moving digital imagery.” Perhaps no other production is more a testament to Milder’s argument than Ivo van Hove’s 2018 adaptation of Paddy Chayefsky’s Network.

The production began its life in London at the National Theater and is currently in previews on Broadway at the Belasco Theater. Network (2018) is part of an ongoing screen-to-stage trend but it is also a watershed moment in its complete integration of digital film technology with the actors’ performances. Director Ivo van Hove and his long-time partner Jan Versweyveld have experimented with live camerawork since the 1990s, creating a hybrid form they refer to as “live cinema.” The Network set takes that concept and uses it to unpack Chayefsky’s prophetic 1976 film by overloading the actors and audience with screens and constantly shifting imagery. Upstage center is occupied by an enormous LED screen which sometimes shows the actors in close-up as onstage camera operators flit around them with choreographic precision. These live broadcasts are then intercut with a variety of “pre-recorded, pre-edited media elements” which, when combined with the restaurant set up on stage right (full of paying audience members) and the control booth full of technicians, engenders an aesthetic that Ben Brantley of the New York Times referred to as “theater as assault and battery.”

This aesthetic of constant inundation and stimulus is apt for a stage adaptation of Network, given the nature of the source text and what it had to say about the insidiousness of media saturation. Because of how perfectly suited Network is to the “live cinema” treatment, it might be tempting to call this integration of cameras and film technology onstage a one-off, but the show’s designer Jan Versweyveld insists that “as video and various forms of media become increasingly more prevalent in our life, I can only imagine that we will stop thinking of [live camerawork] as being something new and something unusual and it will just have a presence onstage the way lighting and sound do in every production.”

What is fascinating to me in the on-going discussion around film and theatre is the accessibility and vulnerability of actors onstage, and how those terms seem to be in the process of revision. Versweyveld justified his and van Hove’s use of live camerawork by saying it was meant “to bring the actors close to the audience.” In the past, the “live” aspect of theater was always presupposed to infuse a performance with a kind of immediacy that could not be replicated on film. However, in an age where technology mediates every part of our lives and proximity to the body (crucially, the face) is almost demanded by consumers, cameras might be the theater’s answer to declining attendance.