Last night on December 6th, the video game industry held The Game Awards, an annual ceremony highlighting the best games of the previous year. The ceremony was like any other awards show. A charismatic host who is well-known in the industry guided the audience through interviews with media makers and occasionally over-wrought skits. Celebrity personalities made jokes and gave out statues to creators whose speeches sometimes ran way too long. A Muppet was there. And importantly, different elements such as sound, performance, and visuals of the medium were celebrated. It was more or less normal—a statement that could rarely be said of past video game award shows. In fact, I argue that last night’s Game Awards represent a paradigm shift toward a maturing video game industry that, like other media industries, has begun to both define itself and legitimate itself through a prestige awards program.

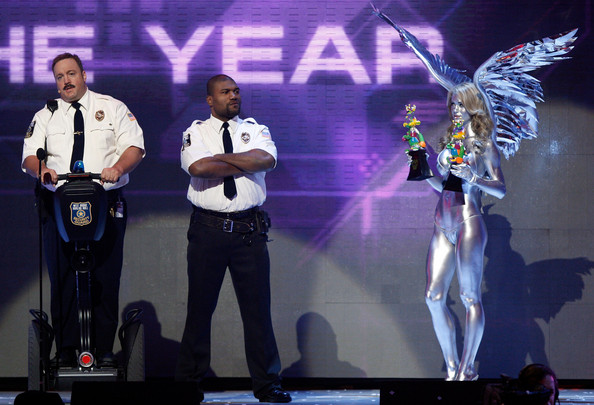

The gaming industry does not have the greatest track record with awards shows. The main awards show outside of industry events were the VGAs/VGX on Spike from 2003 to 2013. These awards were heavy on C-list celebrities, the objectification of women, and baseline male-oriented comedy, but light on actual discussion of video games or attention to the actual awards. Though they drew in Spike’s key audience, the VGA’s were also the target of serious condemnation from both fans and the gaming press. In 2013 host Joel McHale openly mocked game developers and fans, and industry commentators wondered if games deserved better. Polygon’s Justin McElroy and Gamespot’s Danny O’Dwyer both decried what they saw as Hollywood’s clear disinterest in the medium and shallow attempts to capitalize on a popular cultural object they didn’t understand. Kotaku’s Jason Schreier argued that neither gaming’s audience nor the medium were taken seriously by the VGA’s. In a 2011 open letter to the VGA’s producers, he wrote “it’s not hard to find the root of the problem here: You think we’re dumb… You don’t care about the games or the people who made them.”

So what’s changed? For one, space is tight in the era of peak TV, and male-oriented channels like Spike and Esquire Network, as well as the gaming-oriented G4, have all folded. As a result, the video game industry has emancipated itself from television. Producer Geoff Keighley, who has long had a vision for a respected gaming awards show, took the VGAs and rebranded them as The Game Awards in 2014, moving them from cable TV to the internet. Progress in livestreaming technologies means that this ceremony can appeal directly to its audience on platforms like Twitch and YouTube rather than needing to cater to a specific channel’s demographic. No longer produced by Spike, The Game Awards are now guided by an advisory board consisting of representatives from the hardware manufacturers as well as representatives from major studios. The nominations are picked by a jury of 86 media outlets that cover games (including 17 esports-specific sites), and winners are picked by the combined vote of 90% jury votes and 10% fan votes. In other words, this is an event that the industry is creating for itself.

The ceremony has matured as well. The statue, a crucial symbol for an awards show as a whole, has been redesigned from a monkey playing with a controller to a more traditional figure that pixelates near the bottom to reference the medium itself. The Game Awards themselves have moved to the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles, home to the Primetime Emmys and the Grammy Awards. Gags have been dropped in favor of a live orchestra and intimate performances of music from the year’s games. The awards included A-list celebrity presenters like Christoph Waltz and Jonah Hill. They also included a few segments showing the intersection of video games and disability, ethnicity, nationality, and gender to point to the diversifying production culture of digital games. Rather than the commercial advertising structure of television, the Game Awards advertise only new and upcoming games and services. Many viewers view the use of the ceremony to show trailers for upcoming games and announce new titles as proof of the commercialization of the show, which it is to be sure. But is is also an indication that the organizers know their viewership, and through this structure have found a way to bypass traditional exhibition process in a digital-only move that flows with how their audience already experiences the medium.

This isn’t to say that there weren’t surprises, idiosyncrasies, or even cringeworthy gamer references in the ceremony, because certainly the Emmys these are not. But even these moments often sparked joy and reinforced the positive aspects of the community. For instance, fighting game prodigy Dominique “SonicFox” McLean took home the award for Best Esports Player and ended an awkward but endearing speech with what may have been one of the defining quotes of the night, proclaiming “I’m gay, black, a furry—pretty much everything a Republican hates—and the best esports player of the whole year.” Unfortunately, other wins—Ninja taking home the award for Best Content Creator despite accusations of sexism and racism, for example—show just how far the industry has to go. A bigger stage means that these issues may potentially be brought to a wider national audience. Still, as we are all aware, these problems are not unique to games.

Awards ceremonies do more industrial work than just rewarding quality products. They also create a community around the industry, introduce key players, and define star texts. The panel of Sony’s Shawn Laden, Microsoft’s Phil Spencer, and Nintendo’s Reggie Fils-Aimé who opened the show legitimized the ceremony as a representation of the industry. Every industry awards event is essentially a branding exercise. What good awards shows do is lend legitimacy to a medium by claiming that it is an art that deserves to be rewarded. This legitimization does not only lie in the awards being given, however, but in the packaging around them as well. The newfound pomp and circumstance of the Game Awards matter because they show that the industry has begun to take itself seriously, and that audiences are as well. Awards only have meaning if the industries think they do, and the para-industry around awards campaigning shows that the industries think they mean a lot. It appears that the gaming industry may be moving in that direction as well. The Game Awards are an illustrative case study in how contemporary legitimization of an industry through its awards programming takes place, and how that process interacts with audiences and platforms. They may not be the awards gaming deserves, but they are the ones it needs.