We’ve heard you, John Landgraf… there sure is a lot of TV these days. It sometimes feels like analysis paralysis is all but inevitable. Yet Playback’s talented collection of scholarly writers has actually managed to watch quite a bit of television this past calendar year. In this week’s five part TV Round-Up series, they try to make sense of it. Today, Jonathan Gray, Lillian Holman, and Leah Steuer consider the latest seasons of some of television’s most discussed programs.

Westworld

Westworld’s relatively poor reception among media academics and critics perplexes me. Westworld the park is a designed experience, its robot “host” inhabitants programmed to give its “guests” what they want. The cost of this to the robots is that they’re locked into the confines of genre expectation, and the violence this inflicts upon them is shown through the scenes of bullets being wrenched from their bodies, close ups of them being scalped, and so forth. This is preeminently a text about media, in other words, about the violence in audiences’ lust for certain forms of mediated entertainment, about the damage of genre and genre expectation, about what people will actually do, enjoy, adore in a play space. As such, it’s the show that media analysts and critics should be watching. Does it have the “fun” of a Western or scifi show? Sometimes (as with the “Paint It Black” scene in Shogun World), but rarely … precisely because it’s criticizing the horrors of the Western, not holding them up. Looking for the “fun” in Westworld is like looking for the misheard-comment shenanigans in Pleasantville. This world is brutal, because “guests” are brutal (see every scene with Ed Harris). I especially loved “Kiksuya” here, as an episode that addresses the “disappearing” of First Nations people in a way that directly ties this horror to the Western’s papering over of it with stories about Native “savagery.” And the move to Shogun World shows how limited the palette of Othering is, how the desires, the projection, the voyeuristic fantasies imposed upon one space and time so easily transpose to another space and time. Yes, the show is confusing at times, eschewing the prettily-packaged paint-by-numbers plot. It’s atheist television that doesn’t believe in God or easy meaning, much less a benevolent God or meaning. It’s one of the best shows about media in the history of media. Which is why you’re all wrong, and all callous hosts for hating on it. — Jonathan Gray

Doctor Who

At one point in the fifth episode of the new season of Doctor Who, a medical-doctor turns to the titular Doctor and says, “We need more kind people.” If any statement was a central thesis of the show Doctor Who, this is it. This year was especially exciting for Whovians because while the Doctor is technically able to regenerate in any form they wish, every iteration before this year has been a white man. The show therefore made headlines when it cast Jodie Whittaker in the lead role and also brought in a new showrunner, Chris Chibnall of Broadchurch. Now that we are ten episodes in, however, I would say the thing that is most exciting about this new Doctor Who is how it matters much less that Whittaker is a woman and more that she is kind. While the Doctor has never been cruel, Whittaker taps into an older iteration of the character, who is closer to the funny and sincere days of David Tennant and early Matt Smith, rather than the grittier days of late Matt Smith and Peter Capaldi. This is a big difference because these later Doctors have been more concerned with saving the entire universe rather than traveling and helping individuals or small groups of people in need. That difference in scale matters because with smaller episodes, you can emphasize that everyone needs protection, hope, and love no matter who they are or where they are from. The Doctor swoops in to provide that aid and hope, but only because she knows that the people she saves will then save the universe just by being themselves. This conceit is best depicted in the much-celebrated episode about Rosa Parks, but it is a thread that ties the show together. In the end, Whittaker gives us just a bit more kindness every week and, well, we need it. — Lillian Holman

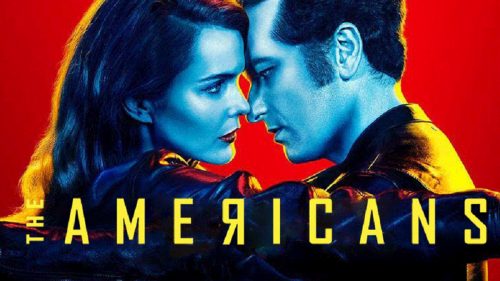

The Americans

What began in good fun and bad wigs ended in death, despair, and ambivalence. Matthew Rhys and Keri Russell were at their career best during six seasons of FX’s criminally underwatched and tightly scripted espionage drama; as covert KGB agents Philip and Elizabeth Jennings, barely masquerading as an average 1980s American couple, Rhys and Russell ignited one another onscreen and served dozens of outlandish (and, occasionally, dumb) spy capers with crackling urgency. The Americans’ narrative, particularly in this final season, tightly interweaves concurrent levels of politics, from international trade tensions to the tender, painful negotiations between partners. The arc somewhat mirrors that of Breaking Bad, another personal favorite about the struggle to hide a secret criminal identity and all the chaos and horror that inevitably attends it. Like Walter White, the Jenningses keep their unwitting enemies close, namely their FBI agent neighbor Stan – whose realization of betrayal is played beautifully by Noah Emmerich in the final two episodes. I particularly loved one recurring storyline around a terminally ill artist, whose paintings serve as a haunting visual leitmotif during the show’s end times. The finale leverages a killer soundtrack (notably U2’s “With or Without You”) towards a devastating and ambiguous end. Almost too stressful to binge, the season is a final hurtle towards reckoning, and – for its performances and technical virtuosity – a thing of lasting value. — Leah Steuer

Riverdale

I love the CW show Riverdale, but like any complicated relationship, I’m not sure whether that is healthy or whether I should just dump it for my own good. Then again, I feel like if I dumped them, I think I would just return because, like Veronica and Archie, we’re “end game.” With every passing season the show gets farther and farther from its iconic comic book roots and has become…well, I’m not sure what it has become. The main characters technically go to high school, and there are enough love triangles to earn its place alongside other teen fare. However, there are some pretty clear homages to Twin Peaks and The Godfather, and I don’t remember Glee having a serial killer. Those are just the peak of the genre mix, though, with others including a musical episode and an extended tribute to The Breakfast Club. If that sounds like it may make too much sense, though, in its third season, it has become an extended narrative about an evil Dungeons and Dragons game. The super fun hitch is that since Netflix’s The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina exists in the same supernatural universe, the game’s Goblin King could actually be a goblin. So maybe I’m high on Jingle-Jangle, but I enjoy not knowing what I’m getting into every week. What I can rely on is that the show commits to each insane storyline with a sincerity that is admirable. Also, the performers are actually the best. Whether it be Camilla Mendes declaring through tears that Archie Andrews is not allowed to leave her, Lili Reinhart’s insane chemistry with Cole Sprouse, Mädchen Amick being the best and the worst at the same time, or Madelaine Petsch doing, well, anything, the people of Riverdale are a joy to watch and, yeah, I’m not dumping them just yet. –– Lillian Holman