Danis Goulet’s (Cree/Metis) film The Hunt is a 6-minute live action virtual reality/immersive film that screened at the ImagineNATIVE film festival in 2017. The film imagines 2167 as a time when automated flying orbs surveil and police North America, including Mohawk territory. A family goes out to hunt on their traditional land and is stopped by an orb. In fighting against the police, the family captures and reprograms a fleet of orbs to only respond to voice commands in the Mohawk language. Goulet’s fictional device invites us to imagine voice activated technologies and computing as a site of cultural struggle, and raises many questions about the politics and possibilities of digitizing Indigenous languages. In addition, the repurposing and remaking of digital tools to fit Indigenous needs may be understood as Dustin Tahmahkera (2017) has described as “sonic sovereignty,” a strategy of Indigenous listening and sound-making that counters the reverberations of colonialism and stereotypical audio cues of Indian-ness.

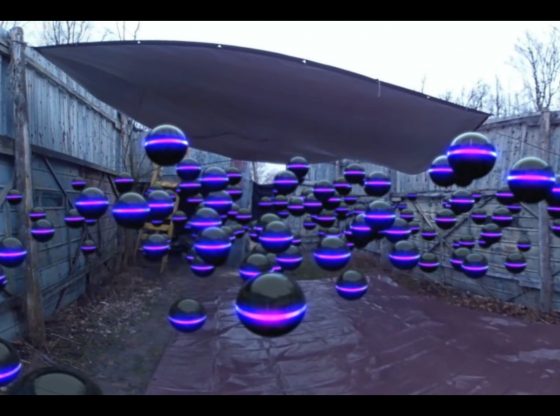

Stills from Goulet’s The Hunt, fleet of voice activated orbs reprogrammed to follow commands in the Mohawk language.

Stills from Goulet’s The Hunt, fleet of voice activated orbs reprogrammed to follow commands in the Mohawk language.

There are close to 800 Indigenous languages in the Western Hemisphere, and Ethnologue reports that there are 195 Native American living languages spoken in the United States, many of which are endangered or at risk. In many of these communities, only a small number of elders are still fluent in the language. The high rates of language loss in Indigenous communities are a result of assimilationist policies, including residential boarding schools where many Indigenous children were sent throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Removed from their homes and communities, children were forced to abandon their traditional culture and forbidden to speak their languages. Today, efforts to preserve and revitalize languages have become top priorities for many communities as an expression of cultural sovereignty and empowerment. In the process, Indigenous communities around the world increasingly utilize digital technologies to support language learners and to integrate traditional language in their everyday lives.

For example, in 2010, Joseph Erb of the Cherokee Nation successfully worked with Apple to add the Cherokee syllabary to its list of supported languages for all iOS devices, the first Native language to be incorporated. He also subsequently collaborated with Microsoft to create a Windows 8 interface pack in Cherokee and to localize Google search engine and Gmail into Cherokee.

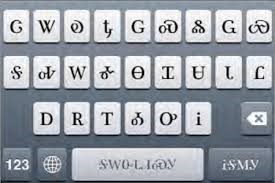

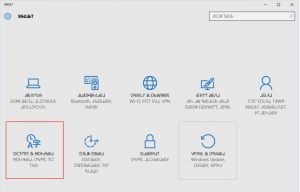

Apple iOS keyboard and Windows 8 interface pack in the Cherokee language.

Apple iOS keyboard and Windows 8 interface pack in the Cherokee language.

Many other communities have also developed installable virtual keyboards, keyboard skins, and online dictionaries with audio files. While these are often tribally specific efforts that reflect community needs and resources, others such as the FirstVoices Keyboard app released in 2016 aims to create software that can serve many Indigenous communities. FirstVoices contains keyboard software for over 100 languages, and includes every First Nations language in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, plus many languages in the USA.

Despite these strides, there are still major technological gaps in supporting Indigenous languages that have yet to be addressed. For example, social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook do not offer language displays in any Indigenous languages, although users can post in-language through the use of keyboard apps. The popularization of voice activated technologies, such as virtual assistants and voice recognition software, are also other avenues to consider beyond integrating text-based language displays and syllabaries.

At the present, Goulet’s vision for appropriating and re-coding voice activated technologies in the service of Indigenous political struggle and cultural sovereignty remains a speculative fantasy. However, it isn’t all that far-fetched. Virtual assistants like Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, and Google Home do not support any Indigenous languages, but companies like Apple and Google both boast a range of supported languages and are constantly working to add more. The process of expanding speech recognition technologies to new languages requires precision and care, but machine learning is becoming simpler and more accurate. Google’s text-to-speech (TTS) system Tacotron 2 is one of the leading tools for creating artificial speech, combining language metadata and intonation features. TTS systems require recording the voices and dialects of native speakers and coding neural networks to classify and predict speech using cultural factors.

There are obvious reasons why voice activated technologies have not become a priority for language activists just yet, though we can consider why interest may develop in the future. At the moment, the uses of smart speakers are fairly benign: conducting web searches, looking up the weather, setting timers, playing music, creating shopping lists, or making calls. Though for many, smart speakers seem like just another tech trend and commodifiable device, virtual assistants and voice activated technologies are often marketed toward older people for ease of use, such as a current commercial for the Amazon Echo Spot. Furthermore, many people with disabilities use voice command systems, and new designs are being developed to integrate voice-controlled features into architecture, classrooms, and communication systems.

Although we can and should explore the possibilities of virtual assistants and TTS systems for a range of groups, these technologies must also be understood as an object of analysis for critical race and digital studies researchers. The rise of sound-based computing and voice interactivity appears to be another vantage point for investigating the digitization of race. As Lisa Nakamura (2007) outlines, the graphic sea change from the early Internet to Web 2.0 brought about a shift from text-based to visual forms, and this altered how users construct and circulate race online, even as it offered new opportunities for marginalized users to participate in their own visual cultures. The increase of online audio content such as podcasts, audiobooks, digital music, and now artificial speech systems may signal a similar turn – or add-on – to Web 2.0 that enables users to speak and listen to race online, and presents new arenas for the formation of minority-produced sonic cultures.

Miriam Sweeney (2017) has written about the racial and gender politics of anthropomorphized interfaces like Microsoft’s failed Ms. Dewey, and recently discussed the gender politics of virtual assistants like Alexa and Siri. In particular, she suggest that designers making a woman’s voice the default setting on these devices reinforces stereotypes about women and feminized labor. In addition, the whiteness of virtual assistants, both in terms of their use of monotone standard English and lack of culturally specific knowledge has been mocked and subverted in a series of YouTube videos such as “If Siri was Mexican” and “If Amazon Alexa was Black: Shameka” along with many videos of users with accented speech attempting to use virtual assistants. These re-imagined virtual assistants respond with culturally specific voices, styles of address, and search results.

Though there is rising demand for more diversity in the voice and language options for virtual assistants, to be clear, simply making a range of voice and language options available will not resolve the issue of racial and gender inequality in these technologies. On the contrary, as Kishonna Gray (2012) has shown, voiced based interactions in digital spaces, such as voice chat in online gaming, are often rampant with linguistic profiling and racist and sexist hate speech that can make such digital spaces extremely hostile for women and people of color. The stakes of sonic difference within digital forms are high and require critical attention on the regulations and algorithmic systems that reinforce such inequalities.

Nevertheless, the productive possibilities of imagining the voiced features/futures of computing technology like Goulet’s Mohawk orb has much to offer media scholars interested in the digital sounds and settings that shape contemporary discourses of gender, race, and Indigeneity. As Jason Edward Lewis (2014) has written,

By engaging in the conversation that is shaping new media systems and structures, Native people can claim an agency in how that shaping carries forward. And, by acting as agents, not only can we help to expand the epistemological assumptions upon which those systems and structures are based but we can stake out our own territory in a common future (p. 63).

Though Indigenous peoples are often ignored or presumed irrelevant to mainstream culture and digital technology, how can we can begin to listen up and ask for more as we imagine the sound of our shared digital futures?